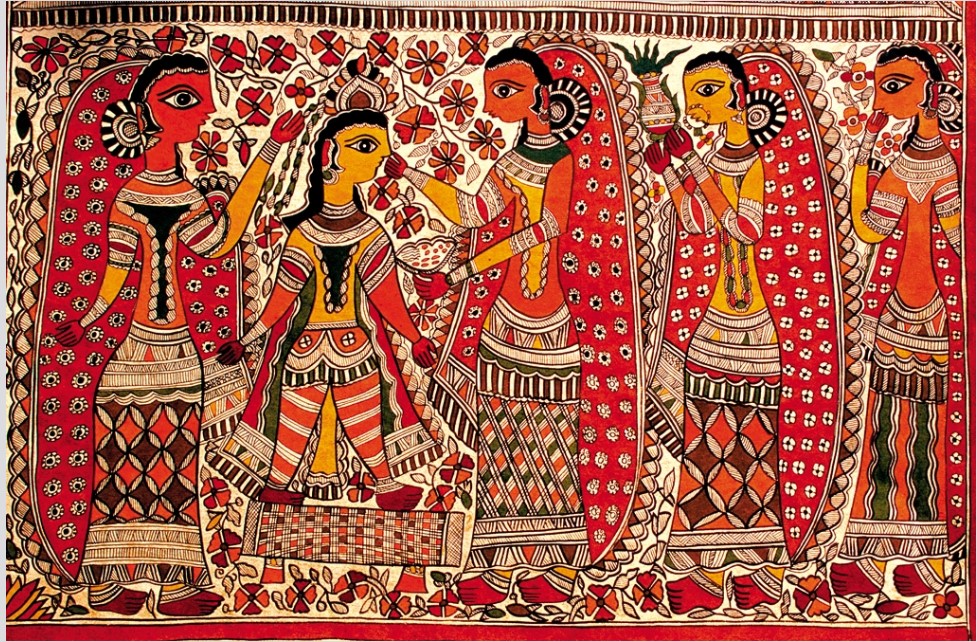

The idea, the word, ‘folk’ has wide range of understanding and connotations – ranging from ‘natural’ to ‘native’ to ‘traditional’ to ‘rural’ and in some cases ‘from the heart.’ The ‘outpourings from the heart’ of native or traditional people later takes the form of folklore.